Climate Change in the Arctic - Impacts of Development on Indigenous Peoples

In the run-up to COP27, we are looking at climate change issues from different angles, from the critical flooding in Pakistan, to the huge environmental and geopolitical impacts in the Arctic. We are extremely grateful for this guest contribution from our friend and colleague at Italy’s Istituto Analisi Relazioni Internazionali (IARI) and University of Lapland PhD candidate Marco Volpe, sent from Rovaniemi in Lapland, where he is researching China’s engagement in the Arctic region.

Global warming is a reality that is hitting the Circumpolar North harder than the rest of the planet.

The fragility of the Arctic ecosystem is revealed by consistent and intertwined threats that climate change brings to the whole region. First, the diminishing of the polar ice cap: in 2021, Arctic sea ice cover reached its annual summer minimum on September 16 and at 1.82 million square miles (4.72 million square kilometers), it was 579,000 square miles (1.5 million square kilometers) smaller than the 1981-2010 average (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2021). The domino-effect related consequences are the risks for specific marine species, for the survival of plants and animals that require favourable snow conditions to survive.

The consequences on the ecosystem obviously are not limited to the Arctic region: the rise of the sea level endangers coastal cities all over the world, the thawing of the Arctic permafrost will not only facilitate the release of carbon emissions stored beneath it, but also represents a real threat to existing infrastructure (urban and industrial) that for a relevant percentage, especially in the Russian Arctic, are dated to the Soviet times, and therefore in precarious conditions.

The last example is the oil spill that occurred in May 2020 when 20,000 tons of oil polluted the Ambarnays river in the area close to Norilsk, in the Siberian Arctic. The dimension of this disaster alarmed Russian authorities and, in terms of seriousness, this accident was second only to one in 1994 when, in the Komi Republic, 94,000 tons of oil were spilt in the Pechora river and later reached the Barents Sea.

Arctic summers are also experiencing a fast increase of Arctic wildfires, especially in Alaska and Siberia, causing evacuations, loss of economic activities and additional releases of greenhouse gas. These are only some general global warming-induced consequences happening in the Arctic, where the paradox of the rise of economic and commercial opportunities collides with dramatic effects on the livelihood of indigenous people livelihood and on the natural ecosystem.

Climate change-related consequences in the Arctic are twofold: they have a global impact and require solutions that are discussed and addressed globally; and their self-feeding nature requires Arctic stakeholders to find a balance between economic opportunities and necessities and the preservation of such a fragile ecosystem

Among the consequences, the melting of the polar ice cap has significant effects not only on the natural environment, but also affects and shapes the geopolitical context of the whole region. The opening up of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) and the increasing possibilities to access invaluable natural resources are just two of the most relevant factors that have led to the scaling up of the region in major powers’ agendas.

Map showing the Northern Sea Route, the Northwest Passage and the Transpolar Sea Route. Map: The Arctic Institute

In the last years as Arctic and non-Arctic countries have drafted and released their Arctic policies, international collaboration under the framework of the Arctic Council’s working groups has helped to address transboundary and transnational issues, and the “Arctic Race” narrative has depicted, perhaps too easily, the whole region as the new frontier for geopolitical confrontation between great powers.

Notwithstanding the escalation of military confrontation discourses in the last decades, the Arctic has experienced years of peace and international cooperation between state and non-state actors that have helped in solving decades-old disputes over sovereignty issues. It was 1987 when Mikhail Gorbachev, leader of the USSR, in his famous speech in Murmansk, imagined the Arctic as a region for peace and collaboration in order to de-escalate the tension between the two blocks.

However, since 24th February 2022, the situation has drastically changed.

The Arctic-7 (USA, Kingdom of Denmark, Canada, Iceland, Finland, Sweden and Norway) have unilaterally condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and with a joint statement have suspended the work of the Arctic Council, whose chairmanship is under Russia until 2023.

Whether states and the private sector may look at the consequences of global warming in the Arctic as an opportunity to meet national interests, Arctic indigenous people are destined to suffer and to adapt their habits to the ongoing and fast-changing reality. “Resilience” is the trendy word to describe the necessity and the capacity to adapt to radical changes happening in the Arctic.

Indigenous people were living in the Arctic region well before the formation of the Arctic States, and their dependence on the Arctic ecosystem is extremely endangered by the neoliberal system that looks at the Arctic as a region valuable for natural resources exploitation and infrastructural development.

The Sami and climate change

If we consider the Arctic region as all the territories above the Arctic Circle, in 2013, there were 4,053,055 people living in the Arctic. The population is ethnically complex and it consists of various groups. Some of them are considered indigenous and some of them non-indigenous groups who migrated to the region. In this article we will speak about the population that live across the Sapmi region collocated across four different states: Norway, Finland, Sweden and Russia.

The estimates of the number of Sami in this part of their traditional territory are quite wide, varying between 50,000 and 100,000 with 40,000 to 50,000 in Norway, 17,000 to 20,000 in Sweden, 7,000 to 8,000 in Finland, and 2,000 in Russia (Pettersen, 2011). Traditionally Sami were hunters and gatherers living in the great parts of northern Russia and Finland. In Sweden and Norway, their traditional area was more extensive than the area used for reindeer pasture today.

When the colonization began, the ethnic balance in Sapmi (the Sámi homeland) changed, turning the Sámi into a minority, except for some parts of northern Norway and smaller areas in Finland and Russia (Axelsson and Sköld, 2011). The key feature of Sami is the nomadic reindeer pastoralism that requires huge and vast territories. The formation of states and national borders across the Sapmi region constituted one of the first threats to the Sami population. The high dependence of the Sami population on the reindeer-herding system has been challenged and endangered many times in the last decades.

One of the changes that deeply worry reindeer herders is the change in snow cover and vegetation, in tundra and mountain range shrub expansion is occurring and the tree line is moving north. The decrease of days with snow cover will facilitate the utilization of other vegetation for forage that will result in raising the productivity of reindeer forage, but the nutritive value will decrease (Turunen et al, 2009).

Snow cover is extremely relevant because it functions as a storage for contaminants and heavy metal pollution, a phenomenon similar to the permafrost that prevents carbon dioxide leakage. Changes in weather are particularly significant for reindeer herders who may face new risks of accidents because of the changes in the carrying capacity of the ice, snow quality and enhanced risks for avalanches.

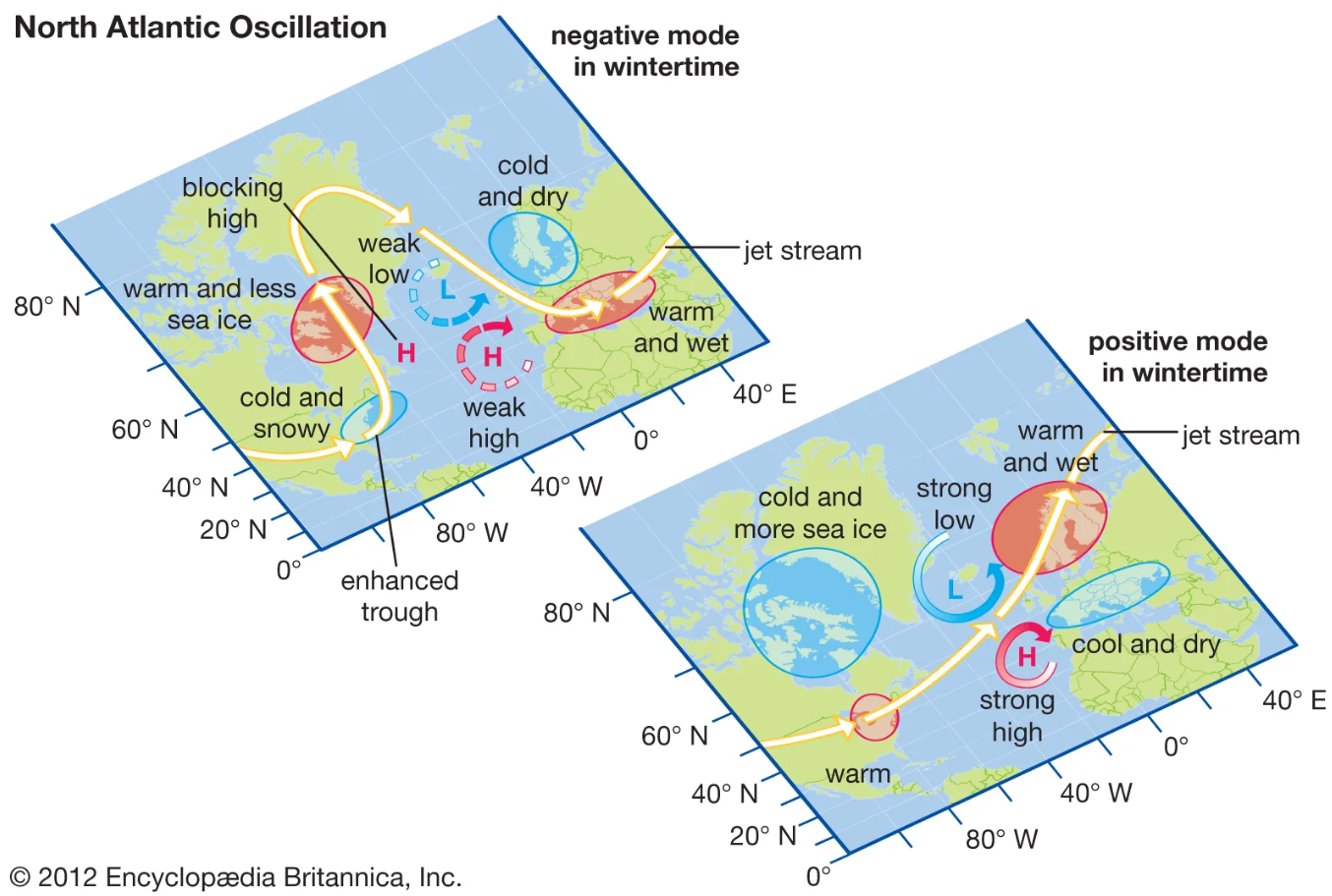

Some changes are induced by the North-Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) which produces mild winters that may promote the development of animal parasite outbreaks among reindeer, animal-borne diseases, and the survival of moths. Even though regional differences do exist, among Sami reindeer herders future expectations and worries related to climate change consequences are shared among the whole community. The unexpected evolution of the highlighted trends along with the difficulty of predicting the time span of such effects also produces anxiety and stress that affects the mental wellbeing of Sami reindeer herders.

In this article we will speak about two different episodes that have challenged the Sami population's livelihoods, and contributed both tothe drafting of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People and to an enhanced role in regional governance.

The Alta Conflict

The Sami population live in the Sapmi region across four different states: Finland, Russia, Norway and Sweden.

Threats to the nomadic reindeer-herding system are not only represented by national state borders between the four countries, but also by the construction of high-impact infrastructure. In 1968 when the Alta hydro power dam project was first announced, it would have flooded the Sami village Máze, endangering the local Sami reindeer herding system. In 1978 the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) had plans to build a dam and power plant on the Alta River in Finnmark in Northern Norway.

The river was extremely important for Sami people for wild salmon fishing and reindeer herding. The construction of the power plant would endanger Sami livelihoods and many Sami coalitions strongly protested against the dam’s construction. The whole protest attracted environmentalists and non-Sami supporters from many different countries worldwide. Camps were set up and protesters started hunger strikes even outside the Parliament in Oslo. Despite the protests, the Norwegian Supreme Court ruled in 1982 that the government had the right to build the dam, whose construction was completed in 1987. Even though the protests could not impede the realization of the infrastructure project, the impact they had on the indigenous peoples’ rights across Finnmark and worldwide was relevant, and also influenced progress towards the UN Declaration of Rights of the Indigenous People.

As an aftermath of the Alta conflict, elected Sami representations have been established in the three Nordic European countries. The first Sami assembly was inaugurated in Finland in 1976 and renamed Sámediggi in 1996, it has 21 seats. The Norwegian 39-seat Sámediggi was inaugurated in Kárášjohka in 1989 and the Swedish 31-seat Sámediggi was established in Giron in 1993 (Oksanen, 2020). Although these have been pivotal outcomes in affirming and defining the Sami’s political status in all three countries, Oksanen (2020) notes how domestically the Sámediggi are incorporated into the nation-state framework rather than being a national Sami institution. The limits of belonging to a nation state’s framework have been also highlighted by Smith (2011) who states how citizenship actually impedes Sami from having reindeer herding bands cross-border arrangements.

The protests against the construction of the Alta hydropower dam also led to the adoption of the Finnmark Act in 2005 by the Norwegian Parliament, that consists in a recognition of the rights of the Sami people as well as the other residents of the Finnmark county.

Photos courtesy of Marco Volpe

The Arctic Railway

The melting of the polar ice cap is contributing greatly to expanding the shipping season along the polar routes. The Northwest Passage mainly goes through Canada’s Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ) and is characterised by the presence of innumerable islands. The transpolar route crosses the Central Arctic Ocean and goes through international waters. The Northeast passage mainly goes through Russia's EEZ. Russia seems to be the most active country in valuing the polar routes because the development of the Arctic region is linked with national interests and the Arctic region provides a consistent amount of energy supply for national demands and for exports.

In the last years, Moscow has launched many different energy projects in the region and the Yamal Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) project perhaps represents the most valuable. The gradual reduction of the polar ice cap eases the passage of ships along the NSR, even though icebreakers are still required to navigate waters in the Russian Exclusive Economic Zone for many months. Before the start of the conflict in Ukraine, the volume of goods shipped along the NSR gradually increased. In 2021 more than 18.7 million tons of LNG were exported from the Sabetta port, in total 263 shipments were completed.

Seasons and environmental conditions play a central role in shaping the geography of the destinations. Sixty of the 263 shipments were directed to France, fifty-three to Belgium and thirty-one to China, which is the preferred destination during the summer season.

The easing of the Arctic’s harsh conditions and the capabilities of the well-equipped Russian icebreaker fleet have encouraged Arctic infrastructural development. In this framework, an Arctic Corridor project has been discussed between Finnish and Norwegian authorities to speed up the shipment from the Nordic region to Central Europe, and an Arctic railway has been proposed to connect the Norwegian port of Kirkenes to the Lapland capital Rovaniemi.

When discussing the project implementation in 2018 the Finnish Minister of Transport and Communications Anne Berner stated that:

“The Arctic railway is an important European project that would create a closer link between the northern, Arctic Europe and continental Europe. The connection would improve the conditions for many industries in northern areas. A working group will now start to further examine the routing to Kirkenes”.

The infrastructure was planned to be built in the Lapland territory of the Sapmi region, posing serious threats to traditional activities of reindeer-herding of the Sami people.

The Sami population strongly opposed the project, stating that for the survival of Sami language and culture preservation of reindeer husbandry, traditional land use and traditional Sami land could be seriously impacted by the construction of the railway. From the Sami side there was a strong request for consultation with the Ministries in order to ensure that Sami rights were protected and respected before taking any decision.

Tuomas Semenoff, from the Väʹččer Reindeer herding district in Sevettijärvi on the Finnish side of the border states:

“The railroad would be a catastrophe for reindeer herding because it will cut our reindeer grazing area in two and it will create a lot of conflicts here”. In 2019 a Finnish-Norwegian working group said cargo was not enough to justify the costs of the project.

In May 2021 The Regional Council of Lapland, decided to rewrite the draft provincial plan for the period until 2040 and the Arctic Railway was not included in the plan. In this case we can see how both skepticism over the viability of the project and concern for preservation of Sami traditional livelihoods guided the regional authorities to drop the project. The decision has been welcomed by the Sami representatives.

Conclusion

Global warming in the Arctic is enlarging the room for business opportunities that states and multinationals are ready to seize. The strong link between indigenous people and the fragile natural ecosystem requires them to rapidly adapt to the constantly changing environment. Preservation of the natural ecosystem is pivotal for all Arctic indigenous peoples and, in the case of the Sami population, actions that alter or modify the natural ecosystem directly impact their livelihoods. The two cases discussed above show how local resistance and the improved role within regional governance have helped the Sami to defend their rights on the land.

However, the suspension of the work of the Arctic Council after the outbreak of the Ukraine war may open a new era of marginalization not only for the Sami population but for all the Arctic indigenous peoples. The isolation of Russia in the Arctic context, where Western sanctions lessen exchanges between Russia and Western countries, may also impact the viability to realize infrastructural projects. Moreover, the EU’s intention to reduce dependence on Russian gas could seriously compromise Moscow’s strategy for the Arctic.

An emerging geopolitical trend sees China as a prominent partner for Russia in realizing its ambitious projects in the Arctic. The relative political stability in the Arctic before the outbreak of the war has helped in addressing challenges posed by climate change. The current global uncertainty not only will impact plans for the Arctic development, but, perhaps more dramatically, may further marginalise the voice of indigenous populations and may slow down transnational collaboration in tackling climate change consequences.

On June 8th the Arctic-7 released another statement on the Arctic Council work that underlines the necessity and the willingness to restore limited circumpolar cooperation in projects that do not involve the participation of the Russian Federation. This statement is particularly relevant to the state's responsibilities to indigenous peoples. Even though it is a small step towards re-starting the discussion and implementation of projects, in the long-term the aim should be to re-engage the Russian Federation within the cooperation framework because of its major role as an Arctic stakeholder and, most of all, for indigenous people that live in the Russian Arctic territory.

References

In: Axelsson, P. and P. Sköld (eds.) 2011. Indigenous peoples and demography: The complex relation between identity and statistics. pp. 185–96. Berghahn Books, New York and Oxford.

NOAA, https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-arctic-sea-ice-summer-minimum#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20Arctic%20sea%20ice,than%20the%201981%2D2010%20average. Accessed on September 9th, 2022.

Pettersen, T. 2011. Out of the backwater? Prospects for contemporary Sámi demography in Norway.

Oksanen, A. (2020). The Rise of Indigenous (Pluri-)Nationalism: The Case of the Sámi People. Sociology, Vol. 54(6). pp. 1141–1158.

Turunen M, Soppela P, Kinnunen H, Sutinen M, Martz F. Does climate change influence the availability and quality of reindeer forage plants? Polar Biol. 2009;32(6):813–32.